ANCESTORS O

F THE FAMILY AND THE FILIPINO AMERICAN WAR

One of the most romantic figures in Philippine history and the youngest general in the Revolutionary Army, Gregorio del Pilar was born on

November 14, 1875 to Fernando H. del Pilar and Felipa Sempio of San Jose, Bulacan. He was the nephew of the great propagandist Marcelo del Pilar and Toribio del Pilar, who was exiled to Guam for his involvement in the 1872 Cavite Mutiny."Goyong", as he was fondly known, enrolled at the Ateneo de Manila where he finished his Bachelor’s degree in 1896, at the age of 20. When the revolution broke out in August under the leadership of Andres Bonifacio, Del Pilar decided to become a soldier of the revolution. Under his command, the Filipinos mounted daring attacks on Spanish garrisons in Bulacan where Del Pilar distinguished himself as a battlefield commander.

The 24 year-old "boy general" led a 60-man Filipino rearguard in the Battle of Tirad Pass against the "Texas Regiment", the 33rd Infantry Regiment of the United States Volunteers. The awesome story has been told and retold with epic grandeur, how Del Pilar stood with his valiant soldiers on the steep and solitary mountain Pass of Tirad, steadfast to repel the invader, or fight and die like honorable men. In a moving eulogy the Filipino soldiers’ "stand against overwhelming odds has been fittingly compared by American contemporary writers to that of Leonidas and his Spartans at Thermopylae, and that of the embattled Afridis at Dargai Ridge. Even now, we are thrilled with the account of their courage. But the death of Del Pilar is something more than a soldier’s death. It was the sublime protest of a patriot against the decree of adverse fate. He had yearned for death when he saw that all was lost for the Republic. He had wished for it when long before the battle of Tirad, he proposed to meet the pursuing enemy after the disaster at Caloocan. He felt its obsession when at midnight on the bank of the river at Aringay he woke up his soldiers and pointedly asked them this question: ‘Brothers, which do you prefer, to die fighting or to flee like cowards?’

"…From morning till noon he repelled charge after charge, he tenaciously held on with his handful of men through the heat and agony of battle, till he himself fell dead among his slain soldiers. And well chosen and most fitting was the place where he offered the sacrifice of his life. It was on the mountain summit, overlooking the plains and the shores of his country, a massive and tremendous altar, built as it were for Titans, caressed by the rolling clouds of morning, lighted by the stars of dusk."

Admittedly, it was one of the darkest hours in Philippine history. A diary belonging to del Pilar was later recovered by the Americans. Its poignant final entry, written on the night of 1 December, read:''"The General has given me the pick of all the men that can be spared and ordered me to defend the Pass. I realize what a terrible task has been given me. And yet I feel that this is the most glorious moment of my life. What I do is done for my beloved country. No sacrifice can be too great."''An American officer, Lt. Dennis P. Quinlan ordered his men to give honor to the fallen but valorous foe, "An Officer and a Gentleman".

Gregorio del Pilar is remembered as the "Hero of Tirad Pass." In that historic place, the young general fought and held back the strong invading Americans with only a few back up men in order to give Aguinaldo ample time to escape from the American military. It was a one-sided battle, but Gregorio del Pilar fought bravely. And he paid for this heroism with his life. He was shot and killed on December 2, 1899 after commanding Aguinaldo's rear guard. Before he died, he wrote, "I am surrounded by fearful odds that will overcome me and my gallant men, but I am pleased to die fighting for my beloved country". The American victors looted the corpse of the fallen general. They got his pistol, diary and personal papers, boots and silver spurs, coat and pants, a lady's handkerchief with the name "Dolores Jose," his sweetheart, diamond rings, gold watch, shoulder straps, and a gold locket containing a woman's hair. But a chivalric American officer redeemed his countrymen's vandalism by giving the late hero an honorable burial and engraved the phrase http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZSH1s-ud64&mode=related&search=

"…From morning till noon he repelled charge after charge, he tenaciously held on with his handful of men through the heat and agony of battle, till he himself fell dead among his slain soldiers. And well chosen and most fitting was the place where he offered the sacrifice of his life. It was on the mountain summit, overlooking the plains and the shores of his country, a massive and tremendous altar, built as it were for Titans, caressed by the rolling clouds of morning, lighted by the stars of dusk."

Admittedly, it was one of the darkest hours in Philippine history. A diary belonging to del Pilar was later recovered by the Americans. Its poignant final entry, written on the night of 1 December, read:''"The General has given me the pick of all the men that can be spared and ordered me to defend the Pass. I realize what a terrible task has been given me. And yet I feel that this is the most glorious moment of my life. What I do is done for my beloved country. No sacrifice can be too great."''An American officer, Lt. Dennis P. Quinlan ordered his men to give honor to the fallen but valorous foe, "An Officer and a Gentleman".

Gregorio del Pilar is remembered as the "Hero of Tirad Pass." In that historic place, the young general fought and held back the strong invading Americans with only a few back up men in order to give Aguinaldo ample time to escape from the American military. It was a one-sided battle, but Gregorio del Pilar fought bravely. And he paid for this heroism with his life. He was shot and killed on December 2, 1899 after commanding Aguinaldo's rear guard. Before he died, he wrote, "I am surrounded by fearful odds that will overcome me and my gallant men, but I am pleased to die fighting for my beloved country". The American victors looted the corpse of the fallen general. They got his pistol, diary and personal papers, boots and silver spurs, coat and pants, a lady's handkerchief with the name "Dolores Jose," his sweetheart, diamond rings, gold watch, shoulder straps, and a gold locket containing a woman's hair. But a chivalric American officer redeemed his countrymen's vandalism by giving the late hero an honorable burial and engraved the phrase http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZSH1s-ud64&mode=related&search=

Si Gregorio del Pilar na mas kilala bilang Ang Batang Heneral,Goyo o ang Agila ay ang pinakabatang heneral na tubong Bulacan na lumaban sa Digmaang Pilipino-Amerikano noong sa taong 1899,nakilala siya dahil sa pagdepensa niya sa kabundukan ng pasong tirad sa Ilocos Sur laban sa mga amerikano,ngunit ano nga ba ang kaniyang naging ambag sa ating lipunan?

Ika-dalawa ng Disyembre sa taong 1899 dito na sumiklab ang labanan sa pagitan ng hanay ni Del Pilar at ang hanay ni Peyton March sa kabunsukan ng Tirad,Ang The Battle of Tirad Pass

Ang US Army 33rd Infantry Regiment, sa pamumuno ni Major Peyton March kinuha ang bayan ng Concepción sa paanan ng bundok ng Tirad noong ika-isa ng Disyembre 1889,minadalian nila na tawirin ang kabundukan ng Pasong Tirad upang putulin ang komonikasiyon ni Aguinaldo sa mga brigada ni Heneral Manuel Tinio na nasa ilog ng Abra at gayundin upang madaling mahuli sa Aguinaldo

Ngunit hindi madalian at nahihirapan ang mga sundalong amerikano na maakyat ang Pasong Tirad dahil denedepensahan ito ng hanay ni Del Pilar na nasa taas ng bundok na ito,maka ilang ulit nila itong sinubukan ngunit bigo sila

On my mother side our ancestors are more famous than my paternal ancestors above. My mother below Angeles del Pilar.....

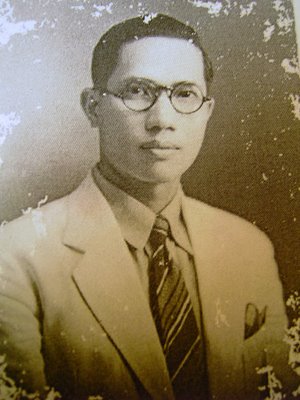

Grandpa Santiago Samson With Friends, notice the piercing eyes and the noble stance that is forever his character

Santiago was a teacher, though I have not met him, (1871-1940) he loomed as a big figure to my mother Angeles. She told me a lot of stories of his exploits in the forest as a hunter, his guiding spirit as a father and his strong gentle character in dealing with his fellowmen.

OUR HERITAGE ON GRANDMA MARIA DEL PILAR SIDE OF THE FAMILY, THAT WE AS HIS RELATIVES, SHOULD ALWAYS REMEMBER TO BE PROUD AND NEVER FORGET THIS GLORIOUS ANCESTOR

My mother above niece of Gen. Gregorio del Pilar, our national hero and grand uncle a younger brother of my maternal grandma., and Marcelo H. Del Pilar an uncle of grandma.

The Samson Brothers, Marceliano was the eldest among brothers, he was the educator of the family and retired from the Bureau of Education.

Marceliano del Pilar Samson (1899-1965) was married to Auntie Anching of Bulacan. One proud anecdote about him was he survived encarceration and torture at Fort Santiago by the japanese during WWII. The execution of prisoners then was in alphabetical order. His savior came timely before his name was called for his execution.

His children's name are Capt. Jose Samson P.N. (deceased) and Dr. Emma Santini (living in Las Vegas)

His children's name are Capt. Jose Samson P.N. (deceased) and Dr. Emma Santini (living in Las Vegas)

Alfredo del Pilar Samson, (1901-1987) the second child of Santiago and Maria, was the adventurer among the brothers. In his young days, he was a professional lightweight boxer in the USA, a US Merchant marine officer, a businessman and a gentleman. His wanderlust never waned, even until his senior years, he traveled the high seas as a ship's master. He was also the best story teller, and the best uncle

I ever had. He died at the age of 86. Alfredo was married to Auntie Isabel Martinez from Santa Cruz, Laguna. His children's name from the eldest are Benito Samson (living in Canada), Cdr. Adolfo Samson P.N. (deceased), Corazon Marcelino (living in L.A. USA), Deogracias "Boy" Samson (living in the PI), Emily Brillon (living in L.A.), Flory (living in the PI).

Enrique del Pilar Samson, the third child of the family of Santiago and Maria. He is the lawyer, businessman of the family. I remember him as the happy go lucky among the brothers, always with a quick wit and a smile. He served in the Philippine Army during WWII, and was able to escaped the Death March in Bataan in April of 1942, with a long time friend and my future father in law Atty. Eulalio Legaspi. Uncle Enrique, left us early in his life, isolated and forlorn to the family due to a severe stroke. He was married to Angeles Topacio. His children's name are Boy, Baby, Ferdinand, Enrique Jr., all are deceased.

I ever had. He died at the age of 86. Alfredo was married to Auntie Isabel Martinez from Santa Cruz, Laguna. His children's name from the eldest are Benito Samson (living in Canada), Cdr. Adolfo Samson P.N. (deceased), Corazon Marcelino (living in L.A. USA), Deogracias "Boy" Samson (living in the PI), Emily Brillon (living in L.A.), Flory (living in the PI).

Enrique del Pilar Samson, the third child of the family of Santiago and Maria. He is the lawyer, businessman of the family. I remember him as the happy go lucky among the brothers, always with a quick wit and a smile. He served in the Philippine Army during WWII, and was able to escaped the Death March in Bataan in April of 1942, with a long time friend and my future father in law Atty. Eulalio Legaspi. Uncle Enrique, left us early in his life, isolated and forlorn to the family due to a severe stroke. He was married to Angeles Topacio. His children's name are Boy, Baby, Ferdinand, Enrique Jr., all are deceased.

It was in the year 1934 that Attorney Enrique Del Pilar Samson and Mrs. Angeles Topacio Samson, an instructor from the National Teachers College founded the school, initially named State Fashion School in a small room at No. 25 Potenciana St. Intramuros Manila.

With the demise of the founders, Atty. Enrique P. Samson and Mrs. Angeles T. Samson in April 1978 and October 1986 respectively, their youngest son Mr. Ferdinand T. Samson took charge of the school’s administration as President and Chairman of the Board from 1987 to the year 1994. However, from the year 1994 to the present, Mr. Aycardo (husband of their only daughter) took over as both President and Chairman of the Board.

On its 70th year of dedicated service, Samson College of Science and Technology stands strongly on a solid and firm foundation, committed to providing the best technical-vocational and computer-based education to the Filipinos.

The Samson Sisters

Correa Samson King one of the Samson Sisters, taken from us early in her life. Mother of Baby Cecille Nickelson

Angeles, Digna, young Alexander, & Agnes (Circa 1953) on her baptism at Espirito Santo Church in Santa Cruz, Manila

http://www.flickr.com/photos/12141389@N00/tags/church/show

http://www.flickr.com/photos/12141389@N00/tags/church/show In Her Own Words "Moments of Love"

In Her Own Words "Moments of Love"Much I have loved you,

But speechless was my love;

The years you spent in my midst

Became a memory

My soul counseled me

To love you,

Like the quiet and placid streams

A flowing love and ardor,

With each caress and full embrace

Knowing the pain of too much tenderness,

I yearn for it now that you are gone;

Yes ever has it been,

That love knows not its own depth,

Until the hour of separation

Who wants to live forever

Ash into ash and to our ultimate origin

Dr. Digna del Pilar Samson was a dentist before she married Atty. Antonino de los Reyes. She was the last survivor among the sons and daughters of Santiago Samson and Maria del Pilar. June 14, 1916 - August 27, 2008 Her progenies from the eldest are Maria Loreto Pahati (1938-2006), Edward Leslie (living in the PI), Rose Delilah Ramos (living in the USA)Stephen Vitus (living in the PI), Aurora Ortenberg (living in the USA), Roxanne Catherine Lyons (living inthe USA), Manolito (living in the USA)

Dr. Digna del Pilar Samson was a dentist before she married Atty. Antonino de los Reyes. She was the last survivor among the sons and daughters of Santiago Samson and Maria del Pilar. June 14, 1916 - August 27, 2008 Her progenies from the eldest are Maria Loreto Pahati (1938-2006), Edward Leslie (living in the PI), Rose Delilah Ramos (living in the USA)Stephen Vitus (living in the PI), Aurora Ortenberg (living in the USA), Roxanne Catherine Lyons (living inthe USA), Manolito (living in the USA)Remedios Samson

Bernardo was married to Juanito Bernardo. Her children's name are Estrella Ferrer (deceased), Edmundo Bernardo (living in Delaware, USA) and Letty Bautista (living in the PI)

Bernardo was married to Juanito Bernardo. Her children's name are Estrella Ferrer (deceased), Edmundo Bernardo (living in Delaware, USA) and Letty Bautista (living in the PI)http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i30HJiy4kY4&search=filipino%20philippines%20bonifacio%20war%20rizal%20revolution%201898%20pilipino%20pinoy%20pinay%20philippine%20flip%20islander%20bayan%20katipunan

Angeles Samson the youngest among the sisters and brothers. This picture depicts her graduation as a teacher, as she was clutching her diploma. The pictures of her children abound in this site with 125 pictures.

The engagement was a two-part battle that started general Elwell S. Otis' Bulacan and Pampanga offensive a day early.[3]: 106 The first phase was a brief victory for the young Filipino general Gregorio del Pilar when he stopped the advance of the American Cavalry led by Major J. Franklin Bell. In the second phase of the battle, Bell was reinforced by the 1st Nebraskan Infantry, who routed the Filipinos, but not before they repelled a cavalry charge that killed Colonel John M. Stotsenburg.

Battle of Quingua

The battle began when US Major Bell with the 4th Cavalry, while on a reconnaissance mission,[4] came upon a strong Filipino position led by Colonel Pablo Tecson, a Revolutionary officer from San Miguel, Bulacan[5] who was under command of General Gregorio del Pilar. The Filipinos laid down heavy fire which halted Bell's cavalry advance. After a short firefight, Bell recognized his position was badly exposed to the opposition, and as a result his force risked defeat. Bell sent for reinforcements, and the 1st Nebraskans came to his aid under Colonel John M. Stotsenburg, while Irving Hale sent companies from the 51st Iowa as well as artillery from the Utah Battery.[3]: 106

Once he arrived on the field, Stotsenburg led the Nebraskan Infantry, with a dozen or so Cavalrymen— in a charge on the enemy's position.[3]: 106 The Filipinos held their ground and opened fire. Stotsenberg was one of the first to fall, a bullet to the heart.[3]: 107 Several of the cavalrymen's mounts were also slain. The Filipino soldiers sustained the heavy fire, forcing the cavalrymen to retreat.

The Nebraskans, only 200 in number, continued advancing under fire by the Filipino riflemen. Despite the accuracy and intensity of the riflemen's fire, the Nebraskan line continued to advance. Inevitably, the two forces clashed in close combat, but after an exhaustive battle, the Filipinos retreated. During the fight, Hale's brigade lost 7 men killed, and 44 more men were wounded.

The engagement was a two-part battle that started general Elwell S. Otis' Bulacan and Pampanga offensive a day early.[3]: 106 The first phase was a brief victory for the young Filipino general Gregorio del Pilar when he stopped the advance of the American Cavalry led by Major J. Franklin Bell. In the second phase of the battle, Bell was reinforced by the 1st Nebraskan Infantry, who routed the Filipinos, but not before they repelled a cavalry charge that killed Colonel John M. Stotsenburg.

Battle

The battle began when US Major Bell with the 4th Cavalry, while on a reconnaissance mission,[4] came upon a strong Filipino position led by Colonel Pablo Tecson, a Revolutionary officer from San Miguel, Bulacan[5] who was under command of General Gregorio del Pilar. The Filipinos laid down heavy fire which halted Bell's cavalry advance.[3]: 106 After a short firefight, Bell recognized his position was badly exposed to the opposition, and as a result his force risked defeat. Bell sent for reinforcements, and the 1st Nebraskans came to his aid under Colonel John M. Stotsenburg, while Irving Hale sent companies from the 51st Iowa as well as artillery from the Utah Battery.

Once he arrived on the field, Stotsenburg led the Nebraskan Infantry, with a dozen or so Cavalrymen— in a charge on the enemy's position. The Filipinos held their ground and opened fire. Stotsenberg was one of the first to fall, a bullet to the heart. Several of the cavalrymen's mounts were also slain. The Filipino soldiers sustained the heavy fire, forcing the cavalrymen to retreat.

The Nebraskans, only 200 in number, continued advancing under fire by the Filipino riflemen. Despite the accuracy and intensity of the riflemen's fire, the Nebraskan line continued to advance. Inevitably, the two forces clashed in close combat, but after an exhaustive battle, the Filipinos retreated. During the fight, Hale's brigade lost 7 men killed, and 44 more men were wounded.

The first important fighting of MacArthur's northward movement was at Quingua (now Plaridel), Bulacan Province, on April 23. It was a two-part battle. The first phase was a brief victory for the young Filipino general Gregorio del Pilar over the American Cavalry led by Major (later Maj. Gen.) James Franklin Bell, West Point class 1878, where Bell's advance was stopped. But in the second phase, Bell was reinforced by the 1st Nebraskan Infantry and the Nebraskans routed the Filipinos, but not before they repelled a cavalry charge that killed Colonel John M. Stotsenburg.

Scouts commanded by Major James Franklin Bell. Photo was taken in 1899, somewhere in Central Luzon.

But in the second phase, Bell was reinforced by the 1st Nebraskan Infantry and the Nebraskans routed the Filipinos, but not before they repelled a cavalry charge that killed Colonel John M. Stotsenburg. Scouts commanded by Major James Franklin Bell. Photo was taken in 1899, somewhere in Central Luzon.

The battle began when Bell (LEFT, 1899 photo) and his men, while on a scouting mission, were attacked by a strong force of about 700-1,000 Filipinos led by General Gregorio del Pilar. The Americans were forced to withdraw to a defensive position. Swarms of Filipino troops began to attack from different directions. Bell saw that he was in a badly exposed position, and if he did not receive help soon his force risked being captured or killed.

The battle began when Bell (LEFT, 1899 photo) and his men, while on a scouting mission, were attacked by a strong force of about 700-1,000 Filipinos led by General Gregorio del Pilar.The Americans were forced to withdraw to a defensive position. Swarms of Filipino troops began to attack from different directions.Bell saw that he was in a badly exposed position, and if he did not receive help soon his force risked being captured or killed.

Mountains of Tirad

Gen. Gregorio del Pilar, P.A.

From morning till noon he repelled charge after charge he held on tenaciously with a handful of men through the heat and agony of battle till he himself fell dead among his slained soldiers. It was on this mountain summit overlooking the plains and the shores of his country a massive tremendous altar.....

To my Grand uncle, I would add to his tombstone as he would say in the end.......

Rest easy, sleep well my brothers.

Know you served your country,

I've witnessed your sufferings,

your job is done.

Rest easy, sleep well.

Others have taken up where you fell,

Freedom will be forthcomming.

Let me bid you peace and farewell...

Philippine American War, The Forgotten War

Percieved Similarities of The Iraq and Philippine Invasions

THE ANCESTORS AND THE FAMILY

Grandpa Eutiquio

The little boy, my father Capt. Amado.............PN, GSC

From morning till noon he repealed charge after charge he held on tenaciously with a handful of men till he himself fell dead among his slain soldiers. On this mountain summit overlooking the plains and the shores of his country a massive tremendous altar.....

Summit at the Battle of Tirad Pass Gen. Gregorio del Pilar rear guard Commanding P.A.

The death of Del Pilar is something more than a soldier's death. It was the sublime protest of a patriot against the decree of adverse fate. He had yearned for death when he saw that all was lost for the Republic. He had wished for it when long before the battle of Tirad, he proposed to meet the pursuing enemy after the disaster at Caloocan. He felt its obsession when at midnight on the bank of the river at Aringay he woke up his soldiers and pointedly asked them this question: "Brothers, which do you prefer, to die fighting or to flee like cowards? |

From morning till noon he repelled charge after charge, he tenaciously held on with his handful of men through the heat and agony of battle, till he himself fell dead among his slain soldiers. And well chosen and most fitting was the place where he offered the sacrifice of his life. It was on the mountain summit, overlooking the plains and the shores of his country, a massive and tremendous altar, built as it were for Titans, caressed by the rolling clouds of morning, lighted by the stars of dusk.

Summit at the Battle of Tirad Pass Gen. Gregorio del Pilar rear guard Commanding P.A.

Gregorio Del Pilar ( PHOTO, ABOVE) was born in San Jose, Bulacan, on Nov 14, 1875 to an illustrious ilustrado (middle class) family. In his early years, he aided his uncle, Marcelo H. del Pilar, in distributing his anti-friar writings. He was a member of the revolutionary forces in Bulacan even when he was studying at theAteneo de Municipal. When the revolution broke out on Aug 30, 1896, he joined the forces of Heneral Dimabunggo (Eusebio Roque). In the battle at Kakarong de Sili, Pandi, Bulacan, on Jan 1, 1897, he almost lost his life.

General Gregorio del Pilar (front, dark trousers) and Filipino army officers in 1898 photo

Del Pilar was promoted to general either in June or July 1898 at the age of 22. (He was the second youngest general in the Philippine army, after General Manuel Tinio). He besieged the town of Bulacan and forced the colonial forces there to capitulate on or about June 30, 1898.

The Filipino-American War found Gen. Del Pilar in the frontlines once again. In the April 23, 1899, battle at Quingua (now Plaridel, Bulacan), he nearly defeated Major (later Brig. Gen.) James Franklin Bell; the cavalry commander, Col. John Stotsenburg, was killed.

Toward the latter part of May 1899, with the Philippine army reeling in the face of unrelenting American offensives, President Emilio Aguinaldo created a peace commission to negotiate an armistice. He appointed Del Pilar to head the Filipino panel. For two days, on May 22 and 23, the Filipinos conferred with the Schurman Commission. The talks failed, owing to the Americans' insistence that US sovereignty was non-negotiable. In addition, the Filipino army had to surrender unconditionally. [RIGHT, photo of General Del Pilar taken on May 22-23, 1899 in Manila].

Mt. Tirad at Concepcion, Ilocos Sur Province. PHOTO was taken in the early 1900s.

Tasked to delay US troops pursuing President Aguinaldo, Del Pilar and 60 of his men formed a blocking force at 4,500-foot (1,372 m) Tirad Pass, Concepcion, Ilocos Sur Province (Concepcion was renamed "Gregorio del Pilar" on June 10, 1955). They constructed several sets of trenches  and stone barricades, all of which dominated the narrow trail that zigzagged up towards the pass.

and stone barricades, all of which dominated the narrow trail that zigzagged up towards the pass.

On Dec. 2, 1899, Major Peyton Conway March (LEFT, as First Lt. in 1896-1898) led 300 soldiers of the 33rd Infantry Regiment of U.S. Volunteers, up the pass. A Tingguian Igorot, Januario Galut, led the Americans up a trail by which they could emerge to the rear of the Filipinos. Del Pilar died in the battle, along with 52 subordinates. The Americans lost 2 men killed.

The Americans looted the corpse of the fallen general. They got his pistol, diary and personal papers, boots and silver  spurs, coat and pants, a lady's handkerchief with the name "Dolores Jose," his sweetheart, diamond rings, gold watch, shoulder straps, and a gold locket containing a woman's hair.

spurs, coat and pants, a lady's handkerchief with the name "Dolores Jose," his sweetheart, diamond rings, gold watch, shoulder straps, and a gold locket containing a woman's hair.

Del Pilar's body was left by the roadside for two days until its odor forced some Igorots to cover it with dirt.

On his diary, which Major March found, Del Pilar had written: "The General [ Aguinaldo ] has given me the pick of all the men that can be spared and ordered me to defend the Pass. I realize what a terrible task has been given me. And yet, I felt that this is the most glorious moment of my life. What I do is done for my beloved country. No sacrifice can be too great."

In World War I, John J. Pershing and Peyton C. March were the American generals who gave the edge to Allied victory over Germany. Pershing was the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) of two million men in France while, during the last eight months of the war, March was in Washington, D.C., as the chief of staff who oversaw the logistics and general development of the army, and the shipment of some 1.8 million troops across the Atlantic. As Secretary of War Newton D. Baker noted shortly after the war, "Together they wrought...victory."

March was born on Dec. 27, 1864 in Easton, Pennsylvania; he died on April 13, 1955 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The St. Paul Globe, St. Paul, Minnesota, Dec. 10, 1899

Monument to General Gregorio del Pilar at Tirad Pass ("Pasong Tirad" in Filipino).

Monument to General Gregorio del Pilar at the Philippine Military Academy, Fort Gen. Gregorio M. del Pilar, Loakan, Baguio City.

Dec. 7, 1899: US Army Realizes End To "Insurrection" Not In Sight

Dec. 11, 1899: Gen. Daniel Tirona surrenders the Cagayan Valley

Soldiers of the 16th US Infantry Regiment (Regulars) haggling with Filipina vendors at their camp in Aparri, Cagayan Province, Cagayan Valley, northeastern Luzon Island. The regiment occupied the valley after the surrender of General Daniel Tirona. Photo taken in 1900.

Battle of Quingua, April 23, 1899

The first important fighting of MacArthur's northward movement was at Quingua (now Plaridel), Bulacan Province, on April 23. It was a two-part battle.

The first phase was a brief victory for the young Filipino general Gregorio del Pilar over the American Cavalry led by Major (later Maj. Gen.) James Franklin Bell, West Point class 1878, where Bell's advance was stopped.

But in the second phase, Bell was reinforced by the 1st Nebraskan Infantry and the Nebraskans routed the Filipinos, but not before they repelled a cavalry charge that killed Colonel John M. Stotsenburg. Scouts commanded by Major James Franklin Bell. Photo was taken in 1899, somewhere in Central Luzon.

The battle began when Bell (LEFT, 1899 photo) and his men, while on a scouting mission, were attacked by a strong force of about 700-1,000 Filipinos led by General Gregorio del Pilar. The Americans were forced to withdraw to a defensive position. Swarms of Filipino troops began to attack from different directions. Bell saw that he was in a badly exposed position, and if he did not receive help soon his force risked being captured or killed.

1st Nebraska Volunteers crossing a river during their advance against the Filipinos at Quingua

Bell sent for reinforcements, and the 1st Nebraskans came to his aid under Colonel Stotsenburg.

Col. John M. Stotsenburg (2nd from left) and some staff officers of the 1st Nebraska Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Photo was taken at his field headquarters in March 1899.

Col. John M. Stotsenburg in the field. Photo was taken on March 26, 1899.

Once he entered the field, Stotsenburg ordered a charge, and the Nebraskan Infantry—Stotsenburg at their lead with a dozen or so cavalrymen—rushed the Filipinos' position. Stotsenberg, taking into account that the Filipinos previously had displayed poor marksmanship, perceived that a charge from such a force would dislodge and route them, which on most occasions, had been done before rather easily.

Instead, the Filipinos held their ground and opened a heavy accurate fire into the charging cavalrymen. Stotsenberg fell, along with 6 of his men. Several of the cavalrymen's mounts were also slain. The Filipinos sustained the heavy fire, forcing the cavalry to retreat.

The Nebraskan infantry advanced under withering fire. Soon the two forces clashed in close range combat. After a stiff fight in which both sides suffered heavy casualties, the Filipinos were driven into their secondary defenses.

Brig. Gen. Irving Hale (LEFT) ordered an artillery bombardment on the Filipinos' secondary defensive lines. Two artillery pieces were brought up, which fired 20 shots into the Filipino positions. The powerful artillery barrage forced the Filipinos to retreat.

Casualties: 15 Americans killed, 43 wounded; 100 Filipinos killed and wounded.

In 1902, a large US military reservation, Fort Stotsenburg, was created in Pampanga Province and named in honor of Colonel Stotsenburg. It was originally set up as a facility for various US Army Cavalry units. In 1919, a US Army air force base, Clark Field, was carved out of Fort Stotsenberg. [The US Air Force became a separate branch of service only in 1947.]

In 1949, the two military facilities were combined and renamed Clark Air Base. It was the largest overseas U.S. military base in the world, with 156,204 acres (63,214 hectares). It played a major role during the Cold War, but was closed following extensive damage from the Mt. Pinatubo eruption on June 15, 1991. On November 27, 1991, the United States turned over Clark Air Base to the Philippine government.

Men of Company D, 3rd US Infantry Regiment, at captured Filipino breastworks that commanded the main entrance to Quingua (now Plaridel), Bulacan Province

Guardhouse of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment at Quingua (now Plaridel), Bulacan Province

Battle of Calumpit, April 25-27, 1899

Issue of April 25, 1899

Brig. Gen. Arthur C. MacArthur, Jr. pushed 5 miles (8 km) farther north of Malolos to Calumpit, where he faced the forces of Gen. Antonio Luna--commander-in-chief of all Filipino forces--and Gen. Gregorio del Pilar.

April 24, 1899: Thirty-eight Filipinos were found dead in this trench near Pulilan, Bulacan Province

Filipino soldiers behind their trenches; photo taken in 1899, probably in Calumpit

Luna ignored Aguinaldo's orders to retreat and burn the railway bridge spanning the Bagbag River at Calumpit. Worst, when the Americans were about to attack, Luna, together with his foot soldiers, cavalry, and artillery left Calumpit to punish General Tomas Mascardo for his insubordination. Mascardo was then in Guagua, Pampanga Province and dillydallied in obeying Luna's order to send reinforcements. Mediators managed to avert a violent confrontation between the two generals.

Bagbag River railway bridge thrown down by Gen. Gregorio del Pilar. The US Army engineers corps built steps for the troops to cross and assault the Filipinos beyond.

During April 23-24, General del Pilar was left to fight the Americans; he threw down a section of the railway bridge. He actually planned to wreck the American artillery transport train; his men cut the girders of the iron bridge, intending to have the structure fall with the train, but it collapsed prematurely of its own weight. The US troops advanced to the edge of the river, a hundred yards beyond which the Filipinos were entrrenched.

The 20th Kansas Volunteers were on the right side of the road and the Utah Volunteer Light Artillery and the 1st Montana Volunteers on the left. In the center was an armored train mounted with six pounders and rapid fire guns.

Chinese porters employed by the US Army in its Central Luzon campaign

The train was pushed by Chinese porters to the mouth of the bridge and a vigorous response was made to the fire of the Filipinos. Col. Frederick Funston, along with 6 men, crawled across the ironwork of the bridge under heavy fire. When they reached the broken span, they dropped into the water and swam ashore.

An armored train with gun used by the Americans at Calumpit

The War in 1900-1901: African Americans in the Fil-Am War

Companies from the segregated Black 24th and 25th infantry regiments reported to the Presidio of San Francisco in early 1899. They arrived in the Philippines on July 30 and Aug. 1, 1899. The 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments were sent to the Philippines as reinforcements, and by late summer of 1899, all four regular Black regiments plus Black national guardsmen had been brought into the war against the Filipino "Insurectos." The two Black volunteer infantry regiments -- 49th and 48th -- arrived in Manila on January 2 and 25, 1900, respectively.

African American soldiers of Troop E, 9th Cavalry Regiment before shipping out to the Philippines in 1900. Up to 7,000 Blacks saw action in the Philippines.

African American soldiers of Troop C, 9th Cavalry Regiment, at Camp Lawton, Washington State, before shipping out to the Philippines in 1900

9th Cavalry soldiers on foot, somewhere in Luzon Island.

The U.S. Army viewed its "Buffalo soldiers" as having an extra advantage in fighting in tropical locations. There was an unfounded belief that African-Americans were immune to tropical diseases. Based on this belief the U.S. congress authorized the raising of ten regiments of "persons possessing immunity to tropical diseases." These regiments would later be called "Immune Regiments".

Many Black newspaper articles and leaders supported Filipino independence and felt that it was wrong for the US to subjugate non-whites in the development of a colonial empire. Some Black soldiers expressed their conscientious objection to Black newspapers. Pvt. William Fulbright saw the U.S. conducting "a gigantic scheme of robbery and oppression." Trooper Robert L. Campbell insisted "these people are right and we are wrong and terribly wrong" and said he would not serve as a soldier because no man "who has any humanity about him at all would desire to fight against such a cause as this." Black Bishop Henry M. Turner characterized the venture in the Philippines as "an unholy war of conquest".

African American soldiers during the Philippine-American War in undated photo. Many Black soldiers increasingly felt they were being used in an unjust racial war. One Black private wrote that “the white man’s prejudice followed the Negro to the Philippines, ten thousand miles from where it originated.”

The Filipinos subjected Black soldiers to psychological warfare. Posters and leaflets addressed to "The Colored American Soldier" described the lynching and discrimination against Blacks in the US and discouraged them from being the instrument of their white masters' ambitions to oppress another "people of color." Blacks who deserted to the Filipino nationalist cause would be welcomed.

One soldier related a conversation with a young Filipino boy: “Why does the American Negro come to fight us where we are a friend to him and have not done anything to him. He is all the same as me and me the same as you. Why don’t you fight those people in America who burn Negroes, that make a beast of you?” Another Black soldier, when asked by a white trooper why he had come to the Philippines, replied sarcastically: “Why doan’ know, but I ruther reckon we’re sent over here to take up de white man’s burden.”

The Black 24th Infantry Regiment marching in Manila. Photo taken in 1900.

One of the Black deserters, Private David Fagen of the 24th Infantry, born in Tampa, Florida in 1875, became notorious as "Insurecto Captain". On Nov. 17, 1899, Fagen, assisted by a Filipino officer who had a horse waiting for him near the company barracks, slipped into the jungle and headed for the Filipinos' sanctuary at Mount Arayat. The New York Timesdescribed him as a “cunning and highly skilled guerilla officer who harassed and evaded large conventional American units.” From August 30, 1900 to January 17, 1901, he battled eight times with American troops.

Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston put a $600 price on Fagen's head and passed word the deserter was "entitled to the same treatment as a mad dog." Posters of him in Tagalog and Spanish appeared in every Nueva Ecija town, but he continued to elude capture.

Page 1, issue of Dec. 9, 1901

The hunters attacked the group and allegedly killed and beheaded Fagen, then buried his body near the river. But this story has never been confirmed and there is no record of Bartolome receiving a reward. Official army records of the incident refer to it as the “supposed killing of David Fagen,” and several months later, Philippine Constabulary reports still made references to occasional sightings of Fagen.

The Indianapolis Freeman, issue dated Oct. 14, 1899, features Edward Lee Baker, Jr., an African-American US Army Sergeant Major, awarded the Medal of Honor for actions in Cuba. Founded in 1888 by Edward C. Cooper, it was the first Black national illustrated newspaper in the US.The article at right, included in this issue although datelined Aug. 18, 1899, describes the movements of the 24th Infantry Regiment while campaigning in the Philippines.

A Black newspaper, the Indianapolis Freeman, editorialized in December, 1901, "Fagen was a traitor and died a traitor's death, but he was a man no doubt prompted by honest motives to help a weakened side, and one he felt allied by bonds that bind."

The Scranton Tribune, Page 1

During the war, 20 U.S. soldiers, 6 of them Black, would defect to Aquinaldo. Two of the deserters, both Black, were hanged by the US Army. They were Privates Edmond Dubose and Lewis Russell, both of the 9th Cavalry, who were executed on Feb. 7, 1902, before a crowd of 3,000 at Guinobatan, Albay Province.

Black and white American soldiers with Signal Corps flag

Nevertheless, it was also felt by most African Americans that a good military showing by Black troops in the Philippines would reflect favorably and enhance their cause in the US.

The sentiments of most Black soldiers in the Philippines would be summed up by Commissary Sergeant Middleton W. Saddler of the 25th Infantry, who wrote, "We are now arrayed to meet a common foe, men of our own hue and color. Whether it is right to reduce these people to submission is not a question for soldiers to decide. Our oaths of allegiance know neither race, color, nor nation."

Although most Blacks were distressed by the color line that had been immediately established in the Philippines and by the epithet "niggers", which white soldiers applied to Filipinos, they joined whites in calling them "gugus". A black lieutenant of the 25th Infantry wrote his wife that he had occasionally subjected Filipinos to the water torture.

Capt. William H. Jackson of the 49th Infantry admitted his men identified racially with the Filipinos but grimly noted "all enemies of the U.S. government look alike to us, hence we go on with the killing."

The Black 24th Infantry Regiment drilling at Camp Walker, Cebu Island. Photo was taken in 1902.

Jan. 6, 1900: US Newspaper Reports Record Incidence of Insanity Among Americans In The Philippines

The Guthrie Daily Leader, Guthrie, Oklahoma, Jan. 6, 1900, Page 1

Jan. 7, 1900: Battle of Imus, Cavite Province

Photo taken in 1900

On Jan. 7, 1900, the 28th Infantry Regiment of US Volunteers, commanded by Col. William E. Birkhimer, engaged a large body of Filipinos at Imus, Cavite Province.

Original caption: "Filipinos firing on the American out-posts, P.I." Photo was taken in 1900, location not specified.

Original caption: "The rude ending of delusion's dream ---Insurgent on the Battlefield of Imus, Philippines."

Four soldiers of Company M, 28th Infantry Regiment of US Volunteers. Photo was taken in 1900. The regiment arrived in the Philippines on Nov. 22 and 23, 1899. It was commanded by Col. William E. Birkhimer.

The St. Paul Globe, St. Paul, Minnesota, Jan. 8, 1900, Page 1

The Americans suffered 8 men wounded, and reported that 245 Filipinos were killed and wounded.

Licerio Topacio, Presidente Municipal (Mayor) of Imus, with two Filipino priests. PHOTO was taken in 1899.

January 14-15, 1900: Battle of Mt. Bimmuaya in Ilocos Sur

US artillery supporting the infantry. Photo taken in 1900, location not specified

On Jan. 14-15, 1900, the only artillery duel of the war was fought in Mount Bimmuaya, a summit 1,000 meters above the Cabugao River, northwest of Cabugao, Ilocos Sur Province. It is a place with an unobstructed view of the coastal plain from Vigan to Laoag. The Americans -- from the 33rd Infantry Regiment USV, and the 3rd US Cavalry Regiment -- also employed Gatling guns and prevailed mainly because their locations were concealed by their use of smokeless gunpowder so that Filipino aim was wide off the mark.

It was believed that General Manuel Tinio, and his officers Capt. Estanislao Reyes and Capt. Francisco Celedonio were present at this encounter but got away unscathed.

Elements of this same 33rd Infantry unit had killed General Gregorio del Pilar earlier on Dec. 2, 1899, at Tirad Pass, southeast of Candon, llocos Sur.

The Battle of Mt. Bimmuaya diverted and delayed US troops from their chase of President Emilio Aguinaldo as the latter escaped through Abra and the mountain provinces. After the two-day battle, 28 unidentified fighters from Cabugao were found buried in unmarked fresh graves in the camposanto(cemetery).

On Dec. 11, 1899, Gen. Daniel Tirona surrendered in Aparri to Capt. Bowman H. McCalla of the US Navy cruiser USS Newark.

The USS Newark in 1899. General characteristics: Length- 311 ft 4 in (94.89 m).....Beam- 49 ft 2 in (14.99 m).....Draft- 18 ft 8 in (5.69 m).....Displacement- 4,083 long tons (4,149 t).....Speed- 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph).....Armament- 22 guns [twelve 6 in (150 mm) guns, four 6-pounders, four 3-pounders, two 1-pounders].

Sixteen months earlier, on Aug. 25, 1898, Tirona, a native of Kawit, Cavite Province, had seized Aparri from the Spaniards. Aguinaldo then appointed him as the military governor of the Cagayan Valley (comprised of the provinces of Cagayan, Isabela and Nueva Vizcaya).

Tirona's surrender was with the honors of war. Captain McCalla (RIGHT, in 1890) reviewed the Filipino troops, and Tirona reviewed the US naval units. The Americans presented arms while the Filipinos were stacking theirs; a total of 300 rifles were turned over.

Captain McCalla appointed Tirona as the temporary civil governor of the Cagayan Valley pending further orders from Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis, 8th Army Corps Commander and military governor of the Philippines.

The Linao Point lighthouse at Aparri, Cagayan Province, 1903. Built by the Spanish in 1896, it was destroyed by a storm and has never been rebuilt.

Manila burns: US soldiers firing at Filipinos, Feb. 23, 1899

The fire, the blare of guerrilla bugles and the shooting confused the Americans. They made their stand on Calle Iris near the Bilibid Prison and waited for reinforcements.

Chinese quarters and business street in Manila. Photo taken in 1898 or 1899.

By now the Binondo market was on fire, but Lucio Lucas --another Luna officer--and his men failed to reach the Meisic police station, his prime objective ((Meisic derived from "Maintsik", which today is Manila’s Chinatown).

The Americans had learned of the planned attack earlier, and were prepared to meet him. Lucas's men retreated towards Calle Azcarraga. In hand-to-hand combat they broke through the American detachment there and disappeared into the night.

The Americans counter-attacked the next day with fresh troops and gunboats. They pushed the Filipinos into Tondo (LEFT, dead Filipinos on a Tondo street). At the tramway station, Paco Roman's men resisted until late in the morning. Others were able to hold a blockhouse but had to withdraw for lack of ammunition.

The Americans counter-attacked the next day with fresh troops and gunboats. They pushed the Filipinos into Tondo (LEFT, dead Filipinos on a Tondo street). At the tramway station, Paco Roman's men resisted until late in the morning. Others were able to hold a blockhouse but had to withdraw for lack of ammunition.On February 24, General Luna reported to Aguinaldo that had it not been for the refusal of the Cavite soldiers to attack when ordered, "our victory would have been complete."

General Otis, horrified by Luna's bold plan, admitted that the attack was "successful in its inception and primary stages."

Aguinaldo took propaganda advantage of the small victory even as Luna accused him of holding back the Cavite soldiers (Aguinaldo's provincemates).

The troops composing the US Eighth Army Corps under General Otis's command by this time were of regulars 171 officers and 5,201 enlisted men and of volunteers 667 officers and 14,831 enlisted men, making an aggregate of 838 officers and 20,032 enlisted men.

Filipino dead at Tondo.

American photograper's caption: "At the battle of Tondo ---work of Minnesota men."

Original caption: "An old man killed while picking chicken in the Filipinos' headquarters in Tondo during the insurgent outbreak."

Luna's attack plan, though a good one, failed for lack of coordination and sufficient firepower. General Luna managed to provide artillery support by using a single Krupp breech-loading cannon firing a six-inch projectile weighing 80 pounds. It was manned by Spanish prisoners with MacArthur’s Headquarters at the house of Engineer Horace L. Higgins as target. Higgins was the general manager of the English-owned Manila Railway Company. This singular artillery piece was neutralized by American counter-battery fire.

A Chinese shop near the carhouse of the Manila Railway Company at Tondo, where the Filipinos barricaded the streets. They fought from inside the wall to the left with the lamp on top.

Bridge in eastern Tondo, fortified by the Filipinos with stone blocks, behind which they fought.

The Annual Report of the U.S. War Department listed 5 Americans killed and 34 wounded; 500 Filipinos killed and wounded.

Original caption: "Minnesota & 23rd Infantry guarding burned district."

Company I, 13th Minnesota Volunteers, at mess, 1899.

Photo published in The St. Paul Globe, Feb. 26, 1899.

"Bomberos" of the Manila Fire Department, Photo taken in 1899. An American artist wrote at the back of this photograph: "Never known to get there on time."

Ruins of Tondo.

Ruins of Tondo; photo includes the American photographer's original caption.

Terra Basta Street in ruins.

Refugees from the fighting and fire at Tondo.

Market scene outside ruins of old market.

Combats between Manila and Lake Laguna de Bay

1899 US Army map of the district between Manila and Lake Laguna de Bay (lower right corner)

With fresh troops from the U.S. mainland, Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis ordered the clearing of the country between Manila and Lake Laguna de Bay, and a push to the north and capture Aguinaldo.

He believed that this move will stretch a line of American troops across Luzon island, thus cutting all communication between the northern and southern wings of Aguinaldo's army.

1899: Review of Company I, 12th US Infantry Regiment, at the Luneta, Manila

U.S. troop strength was 20,851 at the start of hostilities on Feb. 4, 1899; the average strength was 40,000 during the 40-month war (peaking in 1900 to 2,367 officers and 71,727 enlisted men). By war's end, a total of 126,468 American soldiers had served in the Philippines. Also, beginning in September 1899 Macabebe Filipinos --- and in the next two years --- Ilocanos, Cagayanos, Boholanos, Cebuanos, Negrenses and Ilonggos were recruited and served as scouts for the US Army. These regional Filipino scout units were integrated and organized as the Philippine Scouts on Feb. 2, 1901. The Philippine Constabulary was inaugurated on Aug. 8, 1901.

The 3 rifles used in the Philippine-American War by US services---Above, the Winchester Lee, used by the Navy and Marine Corps; in the Center, Springfield, used by most of the Volunteers; Below, the Krag Jorgensen, the weapon of the Regulars. PHOTO taken in 1899.

Twenty-six of the 30 American generals who served in the Philippines from 1898 to 1902 had fought in the Indian Wars. Sixteen graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point died in combat against the Filipinos. Eighty Americans were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Filipino strength at the start of the war was about 20,000 soldiers with 15,000 rifles. In succeeding months, it ranged between 20,000 - 30,000. The number of rifles dwindled as the war dragged on, as many malfunctioned, or were captured by American troops. Ammunition ran low; the Filipinos were forced to manufacture their own cartridges and powder. The makeshift gunpowder lacked power and released thick black smoke that revealed their positions.

The Filipino infantry was tough and hardy, requiring few supplies, and had demonstrated its competence by easily overrunning Spanish garrisons. However, it was relatively poorly trained and the officer corps was weak.

Worst, among the Filipino military and political leaders, disunity caused divisions, usually along regional lines. Although they faced a common enemy who enjoyed vastly superior military training and resources, they still found time to engage in personal, and often bitter quarrels, with disastrous and tragic consequences to the First Philippine Republic.

This color-tinted photo of US soldiers was taken in 1899, somewhere in Luzon Island.

Original caption: "There goes the American soldier and all Hell can't stop him, P.I."

Two members of a US cavalry unit

Americans bury their dead at a graveyard near Fort San Antonio de Abad, Malate district, Manila

The Virginian-Pilot, Norfolk, Virginia, issue of March 17, 1899, Page 1

Battle of Guadalupe Church, March 13, 1899

The Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe church and convent before destruction

Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton (LEFT) led five American regiments against Filipino forces entrenched in the area surrounding the church at Guadalupe, San Pedro de Macati (now Makati City).

Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton (LEFT) led five American regiments against Filipino forces entrenched in the area surrounding the church at Guadalupe, San Pedro de Macati (now Makati City).The official US report listed 3 Americans killed and 25 wounded; it estimated Filipino losses at 200 dead and wounded.

1st California Volunteers positioned near the Guadalupe Convent

US gunboat Laguna de Bay bombards Guadalupe Convent. The side-wheeled steamer used to be a passenger boat that plied the Manila - Lake Laguna de Bay route; Maj. Gen. Elwell S. Otis purchased her from a Spanish firm. Capt. Frank A. Grant of the Utah Volunteer Light Artillery armored the boat and mounted eight guns upon her. The gunboat was about 125 feet long and 37 1/2 feet wide.

Filipinos killed at Guadalupe

The Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Makati City has been renamed as Nuestra Señora de Gracia. The church was completed in 1629. The masonry roof of the church collapsed in the earthquakes of 1880 and the structure was rebuilt in 1882.

Battle of Pateros, March 14, 1899

A battalion of the 1st Washington Volunteer Infantry Regiment under Maj. John J. Weisenburger attacked Pateros on March 14, 1899.

From Taguig, the Americans crossed a channel in cascos and by swimming and stormed the Filipino entrenchments at Pateros. The town took fire and burned. The Filipinos withdrew.

The Americans suffered 1 killed and 5 wounded. Filipino casualties were undetermined.

2nd Oregon Volunteers at lunch near General Wheaton's headquarters, near Pateros, March 17, 1899

Battle of Pasig, March 15, 1899

Pasig: Battery A, Utah Volunteer Light Artillery, commanded by Capt. Richard W. Young, West Point Class of 1882. Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton, sitting among the bananas, and Captain Young, at his back, are watching the progress of the advancing American troops.

Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton attacked the town of Pasig with a Provisional Brigade consisting of: a gunboat, 20th Infantry; 22nd Infantry; two battalions 1st Washington Volunteer Infantry; seven companies 2nd Oregon Volunteer Infantry; one platoon 6th Artillery, and three troops 4th Cavalry.

The Pasig expedition was the first organized campaign against the Filipinos. General Wheaton's instructions were to "drive the enemy beyond Pasig, striking him wherever found".

American losses were 1 killed and 3 wounded. TheNew York Times reported that the Americans found 106 dead Filipinos and 100 new graves near Pasig, and that the 20th Infantry took 175 prisoners. [A separate American report estimated Filipino dead at 400].

Reserves of the 22nd Infantry Regiment awaiting their call to the firing line. They are taking their rest just before the general advance on Pasig.

The 22nd US Infantry awaiting orders for the general advance upon Pasig. The original black and white photo was color tinted in 1902, but the artist incorrectly gave the soldiers blue uniforms; in fact, they were khaki.

Original caption: "The wall of fire. Part of the firing line near Pasig, March 15, 1899. It represents volley-firing in clock-like order at the insurgent intrenchments. The picture was taken just before the general advance." Colorized photo shows 2nd Oregon Volunteers --- armed with 45-70 caliber Springfield "trapdoor" rifles --- correctly portrayed in their blue uniforms.

Skirmish line of 2nd Oregon Volunteers at Pasig

2nd Oregon Volunteers at Battle of Pasig

Original caption: "This shows effect of first smokeless powder used by Americans in the Philippines. The guns are the old Springfield model. Photograph taken during heat of the action at Pasig. In this instance it is long distance firing." This is a colorized version of preceding photo of 2nd Oregon Volunteers.

Skirmish line of 1st Washington Volunteers at Pasig

Skirmish line of 1st Washington Volunteers at Pasig

Original caption: "Taking of Pasig --- In the distance to the left the city is seen, and in front the puffs of smoke from the insurgents' rifles, while half way down the open field the American line is returning the fire, being reenforced by others who are hurrying from the boat on the other side of the river. In the background are the reserve troops who have been protecting the advance."

Original caption: "Driving the insurgents through the jungle near Pasig."

Original caption: "Driving the insurgents through the jungle near Pasig."

Dead Filipino soldiers at Pasig

St. Paul Daily Globe, St. Paul, Minnesota, issue of March 16, 1899, Page 1

US troops in front of church at Pasig

Another view of the church at Pasig. American soldiers, barely visible in the photograph, are seen in the lower left and right corners.

The Pasig Catholic church in 2006. Photo by Elmer I. Nocheseda

Original caption: "The Church Saint Sat On By A Washington 'Johnnie', Pasig, P.I."

American bivouac at Pasig, March 1899.

Two Americans guard a bridge on the main highway at Pasig

US troops returning to Manila after the battle of Pasig

Original caption: "The Washington Boys repulsing an attack of Insurrectos on March 26, 1899, at Pasig, P.I."

Following their defeat in the main battle, the Filipinos occasionally harassed the American garrison at Pasig.

Original caption: "Expecting a Filipino Attack behind the Cemetery Wall, Pasig, Phil. Islds."

Company G of the 1st Washington Volunteers in action at Pasig

Company G of the 1st Washington Volunteers in action at Pasig

Cainta, March 16, 1899

20th US Infantry men returning with their dead; 1899 photo, unspecified location

On March 16, 1899, Maj. William P. Rogers, CO of the 3rd Battalion, 20th US Infantry Regiment, came upon the Filipinos in Cainta, about 1,000 strong, and forced them to retreat. He burned the town. Two Americans were killed and 14 wounded, while the Filipinos suffered about 100 killed and wounded.

The 3rd Battalion, 20th US Infantry Regiment, is drawn up in the main street of Pasig after the fight at nearby Cainta.

Upon the approach of the Americans, Exequiel Ampil, the Presidente Municipal of Cainta and a former agente especial of the Katipunan who had become a pronouncedAmericanista, strongly advised the Filipino soldiers to surrender. Instead, they shot him. Although wounded, Ampil managed to escape.

Issue of March 3, 1902, Page 1

On March 3, 1902, major American newspapers, including the New York Timesreported: “…Felizardo, at the head of twenty-five men armed with rifles, entered the town of Cainta…and captured the Presidente of Cainta, Señor Ampil, and a majority of the police of the town. Señor Ampil has long been known as an enthusiastic American symphatizer, and it is feared that he may be killed by the enraged ladrones. A strong force of constabulary has been sent to try to effect his release.” [Timoteo Pasay was the actual leader of the guerilla band that kidnapped Ampil on Feb. 28, 1902].

A village in the town of Morong, Morong Province. PHOTO was taken during the period 1899-1901.

On March 4, 1902, near the hills of Morong town, Ampil found an opportunity to escape. A detachment of constabulary was taken from the garrison at Pasig and stationed at Cainta for his protection. He survived the war.

[ A considerable number of the population of Cainta are descended from Indian soldiers who deserted the British Army when the British briefly occupied the Philippines in 1762 to 1764. These Indian soldiers, called Sepoys, were recruited from among the subjects of the Nawab of Arcot in Madras, India. They settled in Cainta and intermarried or cohabited with the native women. The Sepoy ancestry of Cainta is very visible in contemporary times, particularly inBarrio Dayap near Barangay Sto Nino. Their distinct physical characteristics --- darker skin tone and taller stature --- set them apart from the average Filipino who is primarily of Malay ethnicity, with admixtures of Chinese and Spanish blood. ]

Battle of Taguig, March 18-19, 1899

The 22nd US Regular Infantry Regiment, 1st Washington Volunteers and 2nd Oregon Volunteers, all under the overall command of Brig. Gen. Loyd Wheaton, engaged Filipino troops led by General Pio del Pilar in the town of Taguig. The Americans suffered 3 dead and 17 wounded; Filipino losses were 75 killed in action.

March 19, 1899: Companies D and H, 1st Washington Volunteer Infantry Regiment, firing at Filipinos from behind the stone wall of the church at Taguig

Some US troops form a skirmish line just outside the church compound

Moments later, the rest of the Americans break out from the church compound to advance across an open field -- Filipinos 800 yards in front.

Original caption: "The Open Field Over Which The Washington Boys Charged The Filipinos From The Church Tower. Taquig, P.I."

March 1899: Company D, 1st Washington Volunteers, at Taguig church.

March 19, 1899: Company H, 1st Washington Volunteers, at Taguig church.

The church at Taguig; US soldiers are positioned behind the stone wall, with lookouts on the roof and bell tower. Photo taken in November 1899.

COLONEL JOHN H. WHOLLE

8

Y, COMMANDING OFFICER, 1ST WASHINGTON VOLUNTEER INFANTRY REGIMENT; HE GRADUATED FROM THE US MILITARY ACADEMY AT WEST POINT IN 1890.THE LOST GENERATION OF DEL PILARS: GOYO’S NOBLE BLOOD LINE

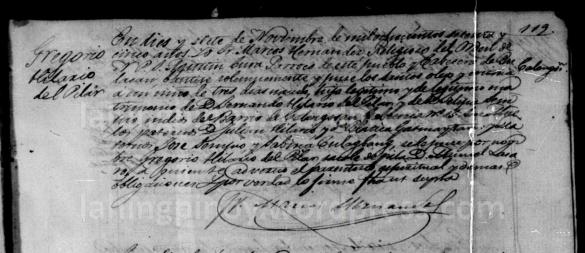

TO RECAP, I FOUND GOYO’S BAPTISMAL RECORD IN THE LIBRO DE BAUTIMOS OF THE OUR LADY OF ASSUMPTION PARISH WHILE I WAS WORKING ON THE SEMPIO CLAN, WHICH HAPPENS TO BE GOYO’S MATERNAL LINE. BAPTISMAL ENTRIES FROM THE LATE 19TH CENTURY OFTEN INDICATED THE CHILD’S GRANDPARENTS, AND SO WAS THE CASE WITH GOYO’S RECORD.

It was the final stage of the tragic death march and a concentration camp with an open field which served as the dumping grave site of Filipino and American soldiers who died with debilitating diseases. It has witnessed the endless sufferings of the sick and the neglected only to die, then dropped in mass with three and half feet depth and those who survived the darkest moments of their lives, they narrated with tears clouding their eyes, the traumatic experiences encountered during their detention, as they gasped with depression and sadness and said CAMP O” Donnell, that was.

An American soldier stands tense in his foxhole on Bataan peninsula, in the Philippines, waiting to hurl a flaming bottle bomb at an oncoming Japanese tank, in April of 1942. (AP Photo) #

Philippines had no significant naval forces after the United States withdrew the Asiatic Fleet following the Attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Philippines had to rely on its OSP with headquarters located at Muelle Del Codo, Port Area, Manila which composed of a high-speed Thorneycroft Coast Motor Boat (CMB) 55-foot (17 m) and 65-foot (20 m) PT boats, to repel Japanese attacks from the sea.During the course of the war, surviving personnel of the Offshore Patrol conducted guerilla hit-and-run attacks against the occupying Japanese forces.

Adolf Hitler, age 35, on his release from Landesberg Prison, on December 20, 1924. Hitler had been convicted of treason for his role in an attempted coup in 1923 called the Beer Hall Putsch. This photograph was taken shortly after he finished dictating "Mein Kampf" to deputy Rudolf Hess. Eight years later, Hitler would be sworn in as Chancellor of Germany, in 1933. (Library of Congress)

The modern world is still living with the consequences of World War 2, the most titanic conflict in history. 70 years ago on September 1st 1939, Germany invaded Poland without warning sparking the start of World War Two. By the evening of September 3rd, Britain and France were at war with Germany and within a week, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa had also joined the war. The world had been plunged into its second world war in 25 years.

A Japanese soldier stands guard over part of the captured Great Wall of China in 1937, during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The Empire of Japan and the Republic of China had been at war intermittently since 1931, but the conflict escalated in 1937. (LOC) #

Japanese aircraft carry out a bombing run over targets in China in 1937. (LOC) #

Japanese soldiers involved in street fighting in Shanghai, China in 1937. The battle of Shanghai lasted from August through November of 1937, eventually involving nearly one million troops. In the end, Shanghai fell to the Japanese, after over 150,000 casualties combined. (LOC) #

First pictures of the Japanese occupation of Peiping (Beijing) in China, on August 13, 1937. Under the banner of the rising sun, Japanese troops are shown passing from the Chinese City of Peiping into the Tartar City through Chen-men, the main gate leading onward to the palaces in the Forbidden City. Just a stone's throw away is the American Embassy, where American residents of Peiping flocked when Sino-Japanese hostilities were at their worst. (AP Photo) #

KISS ME GOODBYE

Caption from 1961: TV viewers of the 1970s will see their programs on sets quite different from today's, if designs now being worked out are developed. At the Home Furnishings Market in Chicago, Illinois, on June 21, 1961, a thin TV screen is a feature of this design model. Another feature is an automatic timing device which would record TV programs during the viewers' absence to be played back later. The 32x22-inch color screen is four inches thick. (AP Photo/Edward Kitch) #

Ocean rescue, as a helicopter lifts NASA astronaut Alan Shepard from the water in May of 1961. (AP Photo)

Adolf Eichmann stands in his glass cage, flanked by guards, in the Jerusalem courtroom where he was tried in 1961 for war crimes committed during World War II. After his kidnapping by Israeli Mossad agents in Argentina, Eichmann was tried and convicted of all 15 charges against him including crimes against humanity, and was executed on May 31, 1962. (AP Photo)

A mob surrounds flaming auto belonging to the U.S. Embassy in Cairo, Egypt on February 15, 1961, after setting it on fire during protest of death of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo. Lumumba was a Congolese independence leader and the first legally elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo. After a power struggle and a military coup, Lumumba was killed by firing squad -- an act many believe was committed with the assistance of the government of the United States and for which the Belgian government officially apologized in 2002. (AP Photo) #

The Japanese ultra-nationalists held their "Patriotic Day" in Tokyo on May 1, 1961, while a record 1,560,000 workers observed the annual May Day celebration throughout the country. Rightists held a rally at Hibiya Park, demonstrating with swastika banner and calling for the dissolution of the Socialist Party. (AP Photo/Mitsunori Chigita/Nobuyuki Masaki) #

The fellows at Homan Hall, Fresno State College's men's dormitory, claim a world record for stacking 73 people on a dormitory bed, on May 17,1961 in Fresno, California, This photo was taken prior to topping the pile with five girls to break the record. (AP Photo) #

An American Apache Indian kneels down to kiss the hand of Pope John XXIII (Angelo Guiseppe Roncalli) during an audience of the Apache delegation at the Vatican in Rome, Italy, May 16, 1961. (AP Photo) #

Actress Marilyn Monroe, as captured by photographer Len Steckler in December of 1961. (AP PhotoPRNewsFoto/Eagle National Mint) #

A dog sits in the middle of an empty Times Square during 10-minute civil defense test air raid alert in New York, on April 28, 1961. Besides the dog, only police are visible in the usually bustling area. (AP Photo/Bob Goldberg) #

U.S. President John F. Kennedy points to a map of Laos during a press conference in Washington, on March 1961, as he states that the communist threat to Laos is "difficult and potentially dangerous". (STF/AFP/Getty Images) #

In this May 1961 dated photo from North Korea's official Korean Central News Agency, distributed by Korea News Service, leader Kim Il Sung is seen together with orphans. (Korean Central News Agency/Korea News Service via AP Images) #

American soldiers of the United Nations Command and North Korean communist guards mix it up following a meeting of the joint Military Armistice commission at Panmunjom, Korea on April 23, 1961. A brief fistfight broke out after one of the North Koreans slapped the face of Pfc. John Clark of Jacksonville, Florida, At extreme left is Capt. William Lyons, of Lubbock, Texas, who joined the fight. (AP Photo) #

An East German worker lays some of the first stone blocks of the Berlin Wall in August of 1961, shortly after the border between East and West Berlin was sealed. (AP Photo) #

East German workers assemble a wall of concrete blocks in the French sector of East Berlin, on August 15, 1961. An East German soldier at the border between East and West Berliners on duty at right. Signs indicate end of the French zone in the city. (AP Photo/Worth) #

Berkeley-O

We have uncertainties about the future, the world was unstable enough, and to live life to the fullest, I have to start a family. In addition to the Vietnam War the United States was being rocked by the Civil Rights Movement and riots in the streets. Western Europe was experiencing a wave of domestic terrorist groups. The Middle East was in turmoil over the Six Day War. Czechoslovakia had tried to liberalize their Communist government and been invaded by Russia. This was the height of the Cold War and the United States and the Soviet Union were nose to nose armed to the teeth with nuclear weapons. There was a lot going on in addition to the Cultural Revolution and Vietnam War.

1960: The picture is indeed Jones bridge going down to what was then Rosario St and is now Paredes St. When you go down the bridge, you reach the first picture. I still remember this place because the RCA building which you can still see in the picture, is where my granduncle used to work. Across this building was what used to be La Estrella del Norte (the jewelry story on the corner of Escolta) and is now Savory Restaurant...Sheila

A refugee from the German Democratic Republic (DDR) is seen during his attempt to escape from the East German part of Berlin to West Berlin by climbing over the Berlin Wall on October 16, 1961. (AP Photo)

A U.S. tank takes position at Zimmerstrasse at the sector border in Berlin, Germany in 1961, pointing towards Soviet tanks across the border in East Berlin. (AP Photo) #

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, wife of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, at work in 1961. (AFP/Getty Images) #

Astronaut Alan Shepard, at left, receives a medal from President John F. Kennedy, with fellow astronauts and Vice President Lyndon Johnson looking on in Washington, D.C. in 1961. (AP photo) #

Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong, atop a camel, enchants the ancient sphinx and pyramids at Giza, near Cairo, Egypt, on January 28, 1961. His wife Lucille, lower left, records the scene on film. The Armstrongs are on a U.S. State Department-sponsored Goodwill Tour of Africa and the Middle East. (AP Photo) #

Billy Stanley, 8-year-old third-grader, the only white pupil at St. Philip the Apostle's school in Albany, New York, studies with African-American friends. Billy says he likes school, and that the other pupils "treat me good." Photo taken on September 19, 1961. (AP Photo) #

Canon John Collins of St. Paul's Cathedral, a leading figure in the campaign for nuclear disarmament which organized the two ban-the-bomb marches over the Easter holiday, addresses a mass protest rally in London's Trafalgar Square on April 3, 1961, after the marchers had converged on central London from Aldermaston and Wethersfield.

Police and secret service struggle in vain to free President elect John F. Kennedy (center) from a surging mass of Harvard students in Harvard yard in Cambridge, on January 9, 1961. Kennedy, normally a fast mover, was halted in his tracks when students broke through police barrier. He had to take refuge in a dormitory until police could bring a car to get him out. (AP Photo) #

Not a car is visible on Malecon Drive in Havana, Cuba, a street well-known to American tourists in former days, as Fidel Castro's forces take over, using it for defense purposes. A single rifle-toting militiaman walks along the drive in Havana, on January 6, 1961, from which all normal traffic was diverted. (AP Photo) #

Fidel Castro sits in a tank during the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April of 1961. Some 1,300 Cuban exiles, backed by the U.S. Government, invaded the island nation of Cuba, attempting to overthrow the government of the Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. The invasion failed disastrously, with 90 of the invaders killed, and the rest captured within 3 days. (OAH/AFP/Getty Images)

Hangars which had been darkened during a strike by airline flight engineers are lighted at Chicago's Midway airport on February 23, 1961, as TWA planes are wheeled out to be prepared for resumption of service. The end of a wildcat walkout against seven airlines was announced in Washington, D.C. by President Kennedy. (AP Photo/EM) #

A giant electrified model of the human brain's control system is demonstrated by Dr. A.G. Macleod, at the meeting of the American Medical Association in New York, on June 26, 1961. The maze of twisting tubes and blinking lights traces the way the brain receives information and turns it into thought and then action. (AP Photo) #

An unidentified student demonstrator is choked by two policemen in Tokyo, Japan, on June 8, 1961, during a clash when police tried to disperse student demonstrators protesting against a controversial anti-political violence bill near the parliament building. Over 10,000 unionists and students took part in the massive demonstration marked by the screaming, rock-throwing and club-swinging clash between the students and policemen. (AP Photo) #

Jean Lloyd, of Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, lost control of her Stanguellini sports car and rolled over in first lap of a 20-lap formula junior race at the Sebring Airport on March 24, 1961 in Sebring. She was not hurt seriously and walked away from the accident. (AP Photo) #

Freedom riders stand at ticket counter of the bus station in Montgomery, Alabama, on May 24, 1961, as they purchase tickets to continue their ride through the south. At center is integration leader Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (AP Photo) #

One of the Freedom Riders being arrested 1961. (AP Photo)

A policeman orders his dog to attack an African-American who was too slow in obeying his order to move away from in front of police court, shortly before nine African-American college students went on trial for sitting-in at a white city library, on March 29, 1961, in Jackson, Mississippi. (AP Photo/Jackson Clarion-Ledger)

George Lincoln Rockwell, center, self-styled leader of the American Nazi Party, and his "hate bus" with several young men wearing swastika arm bands, stops for gas in Montgomery, Alabama, on May 23, 1961, en route to Mobile, Alabama. (AP Photo) #

Moments before photographer Tommy Langston was attacked on May 14, 1961, he shot this single photo of Klansmen attacking a Freedom Rider at the Trailways Bus Station in Birmingham, Alabama. The photo helped identify Klansmen involved in the assault. (AP Photo/Birmingham Post-Herald, Tommy Langston)

National Guard troops enforcing martial law work out with bayonets and gas masks as they go through training maneuvers at Fort Dixie Graves in Montgomery, Alabama, on May 3, 1961. (AP Photo/Horace Cort)

New York Yankees' centerfielder Mickey Mantle completes his swing as he hits his 49th homer of the season in the first inning against the Detroit Tigers at Yankee Stadium, New York, September 3, 1961. (AP Photo/stf)

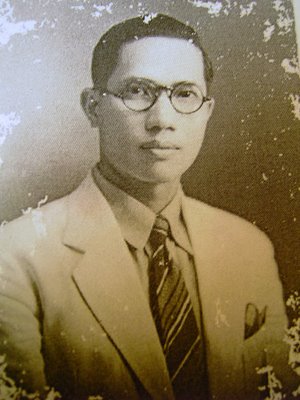

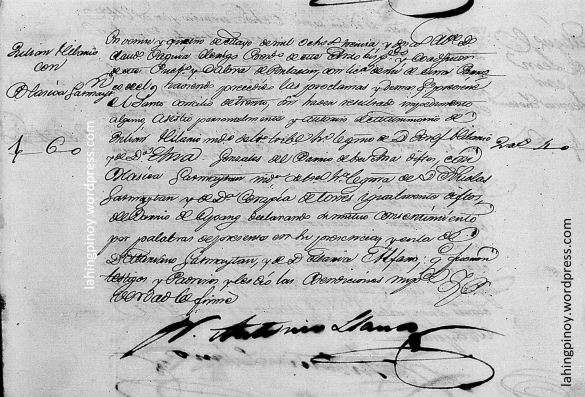

| nd their marriage record in that year.s May 24, 1832. Julian and Blasica were listed as indios, the racial term used in Spanish-era Catholic church records to identify those with native roots. Nevertheless, what’s significant is that they were both of parents who apparently were principales or belonging to the Principalia, the noble (and usually educated) ruling class. This is aside from the fact that Blasica’s last name Gatmaytan may already be an indication that at least her line is of noble lineage. In the lowlands of Luzon, the Tagalog nobility were known as the maginoo. Proper names of the maginoo noble males were preceded by Gat. Hence, we suppose that those with the surnames Gatmaytan, Gatchalian, Gatdula, etc. may have roots from the nobles of Pre-Hispanic Luzon.

Julian is the son of Don Josef Hilario and Doña Ana Gonzales of barrio de Sta. Ana. Blasica is the daughter of Don Nicolas Gatmaytan and Doña Cerapia de Torres from an old barrio named Cupang. Both of their parents were deceased by this time.

So there you have it, a previously unknown generation of the family that produced a number of revolutionaries and national heroes, the del Pilars.

I admire Goyo for his gallant bravery despite his youth, his quick rise to power, and his noteworthy appeal to women. His heritage as shown by ancestral records doesn’t make him any more awesome. He was fighting armies as a general at 22.

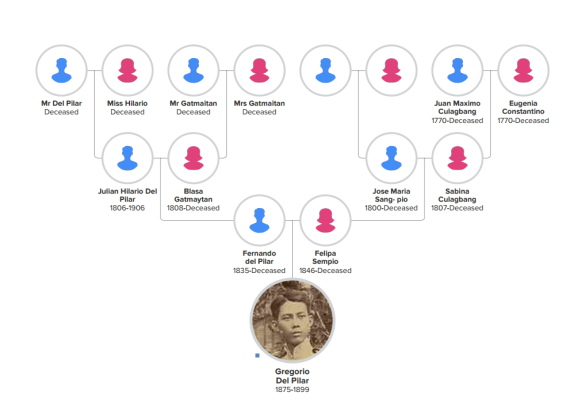

Del Pilar’s Family Tree generated from Familysearch.org The “Boy General” was so called because he was one of the youngest to have earned that rank at 22 years old. He studied at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila, where he received his bachelor’s degree in 1896.